History of the Roxy Theatre and Roxy Cafe, and the creation of the Roxy Museum

.

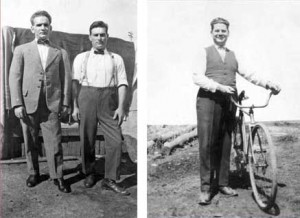

The Greek partners who formed the partnership Peters & Co and built The Roxy. (from right) Peter Feros and George Psaltis. Emanuel Aroney with bicycle. Photo taken 1920s (Photo: copyright Peter Prineas)

The final customers have departed, the tables and chairs have been stacked, the proprietor has turned out the lights.

The dust settles and silence descends. Another Greek Café in another town closes it doors for the last time. Another vacant shop front from another time joins the ranks of those lining the street of another fading community. The passage of time, the final chapter, the end of an era.

The past decade has seen the closure of a number of the last of the Greek family owned cafés in northern New South Wales. The Busy Bee in Gunnedah, the White Rose in Uralla, Fardouly’s Café and Pete’s Place in Inverell to name a few, have recently followed suit. The Paragon in Katoomba and the Niagra in Gundagai, in continuous operation for over a century, are the exceptions to the rule.

It seems the final curtain beckons to those few cafés remaining. Offering little indication of how brightly their spotlight once shone, today they bear only slight resemblance to the period when their appreciative audiences queued for the opportunity to share the magic they brought to everyday life.

Greek cafés left a remarkable legacy on Australia’s cultural history and played a significant role in the changing landscape of our regions. Almost every town across rural NSW and Queensland boasted a Greek café. Depending on the size of the town, any number could be found playing a starring role in the community. The evolution of rural Australia however, has determined that the time has come for these once resplendent pleasure palaces to take their final bow.

There is nothing remarkable about a story regarding the demise of a Greek café in rural Australia. There is something quite extraordinary however, about such a café being brought back to life.

Forty-five years since serving its last mixed grill, The Roxy Café in Bingara, northern New South Wales, is being faithfully restored to its original splendour. Stripped of its original décor and dignity, its respectability is to be reinstated and its reputation restored.

Built by three Greek partners from the island of Kythera in 1936, the Roxy Café was part of an enterprise that included the magnificent Roxy Theatre. The shared narrative of its history exemplifies the Greek migration experience: one that made an outstanding contribution to the development of Australia.

The story of The Roxy is not just about the venue; the bricks and mortar. It is not just about the striking art deco architecture or its historical significance. It’s a story of big ideas, of dreams and visions against all odds. It’s a story of heartbreak and ultimately triumph.

It is a story that has touched many lives and in doing so has been well documented over the years.

Much of the story was played out in the pages of the local newspaper, The Bingara Advocate. Further insights came to light in a Ph.D thesis undertaken in the 1990’s by Kevin Cork, the then President of the Australian Theatre Historical Society. The thesis was entitled Parthenons Down Under, Greek Motion Picture Exhibitors in NSW 1915 – 1960, a topic never before explored in Australian history.

The most comprehensive components of the story however, have been provided by Peter Prineas, the grandson of Peter Feros, one of the original founders of the building, through the extensively researched biography entitled Katsehamos and the Great Idea. A true story of Greeks and Australians in the early twentieth century, the work details the history of The Roxy as a symbol that epitomizes the chapters shared by the two cultures.

.

The Journey Begins

The interior of the Roxy Cafe´taken in the late 1920’s. Seated (front) Peter Feros, (rear) Emanuel Aroney. George Psaltis (standing in white jacket to the left of Peter Feros) Photo: copyright Peter Prineas

The Roxy story begins in the village of Mitata on the island of Kythera in Greece, the birthplace of three men in the 1890’s who later became partners; Peter Feros, Emanuel Aroney and George Psaltis.

Kythera covers an area of 282 sq km and has a current population of around three and a half thousand people. Commencing before the turn of the last century, a large number of Kytherians migrated and the majority came to Australia. Some estimate there may be as many as 100,000 Kytherians and Kytherian descendants in Australia today.

At the time, Greeks were leaving a country that was decimated by war with its devastating effects of political turmoil and social upheaval. Australia was the promised land where the dreams of the destitute and dispossessed lay in the cafés which offered bountiful rewards for the fruits of hard labour.

By the turn of the century, inner city Sydney was home to any number of oyster bars, fish restaurants and refreshment rooms. Those seeking to establish independent enterprises of their own were forced to look further afield. The country towns of New South Wales and southern Queensland embraced these culinary concerns that offered an extensive and affordable array of food, beverages and confectionary to satisfy every pocket.

Like countless immigrants before them who ventured into rural Australia in search of opportunity, the young Aroney, Feros and Psaltis chose Bingara as the town where they hoped to make their fortune. Arriving in the 1920’s to establish a café, they formed a partnership called Peters & Co, a generic business name chosen by Kytherian businessmen who adopted it as an informal franchise among Greek shopkeepers.

Peters & Co were on the road to realizing their dream, despite trading through the years of the Great Depression. During this time of terrible hardship, the food trades were more resilient. There was not much money around, but a visit to the local café was a small luxury people could afford and they savoured it in the hard times.¹

The success of the partners’ business in Bingara is apparent, not just through their decision in 1930 to invest their savings into The Golden Bell, a new café in Barraba. It was also provided by an unprecedented expansion of their business which the Bingara Advocate proclaimed “will herald the Dawn of a new Era in Bingara’s Entertainment history”

The enhancements the partners would make to their business would prove to be no ordinary undertaking. Peters & Co would create an entertainment complex that would remain unparalleled in comparable towns of the region. The enterprise would include a brand new modern café that would seat 140 patrons; three independent shops facing the main street that could leased to ensure the financial viability of the building; a guesthouse to accommodate Roxy patrons, and at its heart, a cinema that would be “the most modern theatre outside of the city.”

The size of the town would not impede the partners’ vision. Bingara, with a population of around 1,500 at the time, would be invited to share their aspirations which knew no bounds in terms of majestic beauty and modernity.

Kevin Cork’s thesis traced the history of 66 Greek cinema owners in NSW from circa 1915 to the early 1960s. A significant number of picture theatre operators were Kytherians who had or continued to run cafés. Their impact on cinema ownership in NSW was immense.

Peters & Co would not be the first motion picture exhibitors in Bingara. Opening in 1912, Bingara Moving Pictures presented the town with silent films accompanied by a pianist. Twice a week, patrons would enter the galvanized iron theatre to take their seats on wooden planks on the gravel floor, or on the dearer seats at the back built up on tiers.

A second silent picture show would open in the Soldier’s Memorial Hall in 1931. Local businessman, Victor Reginald Peacocke, was the presenter of the cinema he named the Regent Theatre. In 1934, around the time that Peacocke introduced Bingara to the first talkie pictures ever seen, Bingara Moving Pictures was consumed by fire and burnt to the ground.

Unlike the modest cinemas Bingara enjoyed, Peters & Co engaged Mark Woodforde, a Sydney architect, to build a picture theatre that could suitably house a palace of dreams. The auditorium would be 104 feet long from the rear wall to the stage and 40 feet wide, with a drop from ceiling to floor of 24 feet. There would be steps in the vestibule area to gain height; this would allow the floor of the auditorium to slope down towards the screen and provide every patron with a good view. The sloping section of the floor would have seating for 280 customers and the level section closer to the screen would accommodate another 470. The level area was designed so that the seats could be removed, revealing a large dance floor made of beautifully joined timbers cut from the cypress pine forests of the north-west.²

.

Cinema Wars

Peters & Co’s plans incensed Victor Peacock who was determined to rule supreme in the cinema stakes. In a letter to his local Member of Parliament, he painted a scene of Greek standover men running amok in quiet little Bingara. His letter contained the declaration that he would in fact build his own cinema stating “I have no intention of allowing the Greeks to put it over me in this way, so I am endeavouring to get in ahead of them… I shall be submitting plans myself during the next few weeks…and I am hoping those of the Greeks will be held up until I can get a start.” Peacocke was determined to open before Peters & Co and was elected to Council in the interim.

Victor Peacock’s modest Regent Theatre opened in June of 1935, just 18 weeks after the building was approved. Peters & Co would take another nine months to open their doors after a series of continued setback through Council approvals.

Peacocke also sent off another letter to the Chief Secretary of New South Wales who was responsible for the regulation and licensing of picture theatres requesting that a building inspector be sent up from Sydney to find something ‘untoward’ with the plans of the Greeks. Fortunately, the Department in Sydney didn’t comply with Peacocke’s requests and on the evening of Saturday 28 March 1936, the opening of The Roxy was unlike anything Bingara had ever experienced.

The Bingara Advocate reported that “probably no event in the history of Bingara has caused more interest and excitement.” Prior to opening time “it was impossible to wend one’s way through the crowd” which ‘stormed the streets’ the paper reported. Officially opening the new premises, the Mayor declared the theatre to be a ‘monument to the town and one of the finest buildings of its kind outside the city.’

And so began the ‘cinema war’ between Bingara’s rival theatres with the intense competition that ensued. The pages of the Bingara Advocate provide fascinating documentation as they provide an invaluable record of the films that were screened, including the cartoons and the clubs that they formed. They also allow us to experience first-hand the unfolding battle between the two cinemas as it is played out amongst its pages.

An advertisement placed by The Regent, three weeks after The Roxy’s opening, announced a special bargain night, when the price of admission would be one shilling all over the house, including children at half price. Accordingly, The Roxy is forced to do the same.

The Roxy then hits back, holding a Movie Ball which it declares “will be the most spectacular dance event in Bingara’s dance history…. That “Uncle” George Psaltis declares he is going as Shirley Temple, and has been measured for a special dress.”

Even the spectacle of George Psaltis in a dress and wig full of Shirley Temple curls was not enough. Other marketing ploys were tried, including the offer of “A one pound reward for any lady who will sit alone in the theatre for a midnight screening of the Black Room with Boris Karloff.”

Intense competition led to various promotional ruses. The most telling was the installation of two large loudspeakers on top of the Roxy’s parapet. These were part of the theatre’s RCA public address system and were used for competitive spruiking and to broadcast announcements, music and film soundtracks to the town’s residents.³

Peacock continued to make improvements to his Regent Theatre such as upgrading his sound equipment that became far superior to that of The Roxy. His greatest innovation however, was the opening of the outdoor picture gardens. This would be accomplished by building a projection box on the existing rear wall of the theatre while mounting the projectors on swivels. The audience, in their canvas seats, could then enjoy screenings under the stars in the area located directly behind the theatre.

With or without the picture garden however, the end had come for Peters & Co. In mid-August, just five months since they had opened their doors, the theatre, the café, the shops and the guesthouse were all lost. There were many debts to cover the vast expense of building The Roxy and in September 1936 the three partners signed for bankruptcy. They had lost everything they had worked for since coming to Australia.

Peter Feros moved to Murtoa in the Wimmera district of Western Victoria where he would begin the long journey of attempting to recover his fortune through the purchase of the Marathon Café in McDonald Street. He was eventually joined by his wife and remaining children in Murtoa where he would live out his days.

Emanuel Aroney remained in Bingara where he was joined by his two sons. He would continue to manage cafés in the town for the following twenty years before retiring to Sydney.

After a stint in Sydney, George Psaltis returned to Bingara to manage The Roxy Café for a time before returning to Sydney to establish the Q Café in Kings Cross. In the 1950’s he moved to Adelaide where it is reported he died alone and penniless.

From all accounts, it appears that George Psaltis was more inclined to entrepreneurial flights of fancy than his two partners. It may well have been his vision to build The Roxy Theatre, and it is likely that he was the driving force behind it. He was not an astute businessman however, and his vision may not have been shared by his partners.

.

A Sleeping Beauty

The Roxy Theatre operated as a cinema until 1958 when it shut down. Apart from the occasional films screening, odd boxing match or roller disco, it would spend the next forty years virtually lying dormant. A new generation was growing up in the town having never stepped foot inside it. They may well have walked past the façade every day of their lives, with little clue as to the grandeur that lay within.

The Regent Theatre was well patronized through the 1950’s and 1960’s and continued to operate until the 1970’s. Since 1981 it has housed the Bingara Civic Centre.

The Roxy Café continued to operate under a series of Greek owners until the mid-1960’s when it became a freehold title and was sold to Bob and Elva Kirk who opened a memorabilia shop in the café, and who lived above it in the residence. It then fulfilled a rightful obligation to every small town when it masqueraded as a Chinese Restaurant for twenty years before being purchased by the Gwydir Shire Council in 2008.

The purchase of the freehold title of the café completes The Roxy picture. Prior to this acquisition, it was a group of dedicated community members in the early 1990’s who first recognized The Roxy’s significance and began to lobby the then – Bingara Shire Council to purchase and restore the theatre. The Bingara Council purchased the building in 1999 and once it had been successful in obtaining both state and federal funding, set about faithfully restoring it to its former glory.

While the story ended sadly for our Greek founders, it has ended triumphantly for us. The Roxy stands in its original state, as testimony to the legacy of what the three partners have left behind.

The Roxy officially reopened its doors in 2004. It is owned by the Gwydir Shire Council and operates as a multipurpose cinema, performing arts venue and function centre that includes a variety of conferences, seminars, weddings and private functions. It also houses the Bingara Tourist Information Centre and is open to the general public for tours. Above all, it belongs to the community and is accessed by the community for numerous events and activities.

Cultural activity plays a vital role in our lives, particularly for those who live in more remote, isolated communities. Through theatre, music, dance, we are able to reflect the social and economic challenges that surround us. The arts give us a sense of identity and a sense of our selves. They are a key component in the livability of our communities and are vital in attracting and retaining people to these communities.

The Roxy takes pride in continuing to uphold the prized values espoused in an advertisement placed in the Bingara Advocate in 1936 which reads: “With its atmosphere of refined luxury and perfection of service, the Roxy stands as a worthy landmark of progress and a monument to the progress of a Worthy District.”

.

The Final Chapter

In 2009, the Gwydir Shire Council was the recipient of a grant for $750,000 through the Department of Heritage, Environment, Water and the Arts under the Australian Government Jobs Fund, primarily to restore the Roxy Café.

A museum celebrating Greek immigration to rural Australia will be incorporated into the project. It will pay tribute to the remarkable legacy of the Greek cafe by recognising the significant contribution Greek immigrants made to the changing landscape of rural Australia.

Greek cafés changed the course of Australia’s cultural history and left a significant legacy on our culinary and cultural landscape. Very few Greek cafes operate as they did 50 years ago. Even fewer complexes that incorporate a functioning cinema and café remain. Once complete, The Roxy may be the last purpose built theatre with adjoining café operating in New South Wales.

The Roxy Café will become a place of national significance that conserves and protects the important cultural associations between people and place. It will provide opportunities for the celebration of Greek traditions that became embedded in Australia.

The work carried out in the restoration will be undertaken to best protect the significant fabric of the place with minimal disturbance to ensure the culturally significant aspects of the place are respected, retained and preserved.

The restoration of the Café will include the re-instatement of furniture of the period that has been acquired for the purpose, including a 35ft counter with original soda fountain, as well as custom-made display cabinets and shelving which have come from the Farouly’s Café in Inverell. The original wood paneling as well as the original booths from the Roxy Café will be reinstated, having spent the last forty years securely stored in the shed of a local resident. In a paddock not far from the shed, the original neon shop sign that hung under the awning was found, waiting for the day when it would light up once again and take its place at centre stage.

Architectural firm Magoffin and Deakin from Armidale has been appointed to the project. Heritage architect Anthony Deakin was responsible for the restoration of the Roxy Theatre carried out in 2003.

The café will be leased to a commercial operator who will work in conjunction with the Gwydir Shire Council to achieve the collectively desired outcomes. Expressions of Interest to manage the Café are currently open.

The refurbished Roxy Theatre is a multi-purpose venue and here it is used for a dinner. (Photo: M. Metzke)

The Roxy will become a place of great historical significance that exhibits local distinctiveness and a sense of place. Its civic pride and confidence in its heritage, in its cultural facilities and collections is destined to attract people from all walks of life, all wanting to share this unique experience.

It is interesting to note that The Busy Bee in Gunnedah recently ceased trading and permanently closed its doors. The significance of the café has been recognized however, and the entire collection has been acquired by the National Museum in Canberra for its archives.

In order to do justice to this important chapter of Australian history, the Roxy welcomes relevant contributions towards its museum and would be most grateful to receive items of café and cinema memorabilia to ensure the success of the project. All contributions received will be acknowledged.

In his thesis Kevin Cork advised us that: “If we are to remember these Greeks for their contributions to Australia’s social, architectural and technological advancement, then it is imperative that there be Greek landmarks which are acknowledged at local and state level – ones that point to the achievements of the Greek-Australian cinema exhibitors… We cannot allow their histories to be forgotten, not when they provided services that positively affected millions of people, firstly, through their refreshment rooms and, secondly, through their picture theatres.”

We intend to do just that, as the final chapter of the Roxy story is destined to live on for generations to come.

Sources:

P. Prineas. Katsehamos and the Great Idea. A true story of Greeks and Australians in the early twentieth century. Plateia. 2006

T. Risson. Aphrodite and the Mixed Grill: Greek Cafés in Twentieth-Century Australia. T. Risson. 2007

¹ P. Prineas. Katsehamos and the Great Idea

² P. Prineas. Katsehamos and the Great Idea

³ P. Prineas. Katsehamos and the Great Idea

Black and white photos are copyright to Peter Prineas